His eyes wide shut

Imagine yourself a young man of 18. Not even quite 18 yet, so appropriately excited. You have travelled around Europe and arrived back from Gottingen inspired. You are a worshipper of Kant, you are a poet of great sentimentality and every bit of a Romantic ideal. Your tongue is enthusiastic, your mind is full of idle liberal ideas, your cheeks are rosy and your dark curls are long. Your name is Vladimir Lensky and you find yourself in an empty family manor in the middle of Russian nowhere.

Now, to someone like myself that would be the beginning of a deep and long relationship with depression. But, surprisingly, not for Vladimir. Not only is he unaffected by the boring predictability of a remote Russian province, he thrives there and his cheeks never lose their colour. There are a few reasons for that.

First and foremost, as a true poet, he is deeply in love with the one and only – his childhood sweetheart (in the words of Bridget Jones, they have been running around the same swimming pool). This love is painting the world around him in fluorescent colours evasively protecting him from reality.

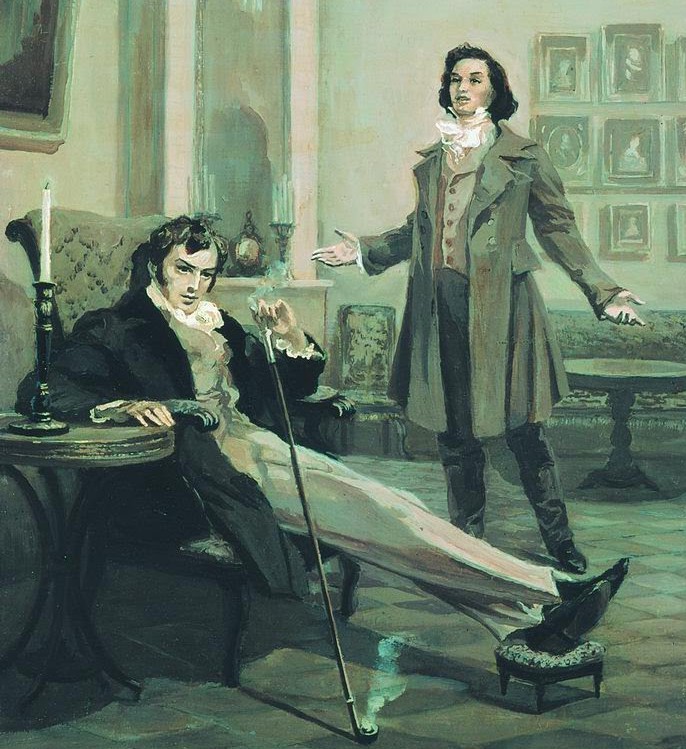

Second, he meets a new neighbour. Only a few years older, but so much more, so to say, tired of life, that he must be wiser. They are like “earth and water, prose and verse, ice and flame” but they share education, interest in books and mutual disappointments: one – his lovesickness, another – his sickness of pretty much everything else. They drink together most evenings, discussing deep philosophical matters. Within months one will kill another.

But beyond his love for Olga and his friendship with Onegin, there is still one more reason why Lensky is perfectly content to combine his limited existence with his unlimited ideals. What if for just a moment we could imagine that the duel had not happened? That Onegin (Vladimir wouldn’t have, he is a poet after all) had come back to his senses and refused to fight. He’d shaken Lensky’s hand, had swiftly departed from the unfortunate birthday party and sent a note to his friend in the morning suggesting some shooting together in his woods to seal the peace treaty. What would have happened to Lensky if he had a chance to grow up properly?

My name isn’t Cassandra, but I will tell you. To the great delight of madam Larina, our Vladimir would marry Olga, who would get bored of him within a few months and would start flirting away at every opportunity. At first her husband would get a bit of passion going, but then would get comfortable and decide that the trouble is not worth the hassle. He would, no doubt, become a good master of his land and people, applying his old German education trying to improve his peasants’ lives. But German principals do not take well to the Russian soil, and Lensky’s idealistic setups would fall through one after another. He would still read, but less and less of Kant and more and more of “Horse and Hound”. He would still dream but less and less of undying love, and more and more about tomorrow’s dinner. Because our Lensky is only a little local gentleman, slightly poisoned with western Romantic ideas, but longing really for a nice wife and a few little rosy-cheeked kids. And let’s face it: as a poet, he is pretty mediocre.

What makes him the Lensky we love is the duel. Untimely death for no reason but the arrogance of youth that knows not that death is real.

For there, where the days are short and overcast,

Lives a race of people for whom death is no pain.

Petrarch

Love never consummated. Kisses never received or given. Romantic ideals never pursued and never betrayed. It was not his choice, it would not be his choice, but caught a victim of his own romanticism, Lensky dies with his eyes wide-shut to the realities of the world. And with surprise and disbelief he bids farewell to his youth and to his life: “Kuda, kuda, kuda vy udalilis’…” – where are you gone, oh days of my golden spring?

P.S. Look through our opera files to find transliteration and audio reading for Lensky’s aria.

Opera:

Categories: Blog post